Our history

We have been at the forefront of exploring mental health and wellbeing since the First World War. Our history informs our mission and our values – we work to pioneer the development and delivery of effective clinical interventions, and to be a national and international centre of excellence for training and education.

Attachment theory

John Bowlby had been one of the original members of staff at the Portman Clinic, but at the end of World War 2 he joined the Tavistock and became the Head of the Children’s Department. It was here that he carried out work that would eventually lead to his three volume treatise on attachment. Bowlby’s ‘trilogy’ – Attachment, Separation, and Loss – had, by 2010, been cited over 12,000 times. By this measure at least, John Bowlby is the most influential psychoanalyst of all time, establishing a new developmental paradigm.

Mental health services have gone through a radical transformation over the past 100 years – perhaps more so than any other part of the health system. A model of acute and long-term care based on large institutions has been replaced by one in which most care is being provided in community settings by multidisciplinary mental health teams. These teams support most people in their own homes, and elsewhere in the community (e.g. schools) but have access to specialist hospital units for acute admissions and smaller residential units for those requiring long-term care.

A history in the making by you

From our inception through to the present day, everything we do is with thanks to all of our extraordinary staff.

From our outset, we sought to prevent the hospitalisation and institutionalisation of individuals who might live useful and productive lives. We treat people across their lifespan and have expanded the understanding of mental health with our developmental approach. This has led to work with an ever-increasing range of professional groups. We have provided a century of original and innovative thought on human development and how to support those that need help.

Our pioneering models of care

We have been at the forefront of exploring mental health and wellbeing for over 100 years.

Our history through the years

1920 to 1929: Our founding

The Tavistock Clinic saw its first patient, a child, on 27 September in 1920. Its name was taken from its original location at 51 Tavistock Square. The Clinic was established by Hugh Crichton-Miller, with contributions and pledges from wealthy donors and started off with seven doctors.

Hugh Crichton-Miller’s aim was to provide civilians with the kind of treatments that he and other doctors had developed while working with shell-shocked soldiers during World War 1.

Initially, the Tavistock Clinic was meant to be a three-year project to demonstrate these methods, which would then be taken up by out-patient departments in mainstream hospitals. However, the Clinic did not close, it grew.

The Tavistock Clinic originally had two departments: Adult and Children’s. At the time having a separate children’s department was quite revolutionary and anticipated the work of Child Guidance Clinics by several years.

Almost from the outset, education and training were part of the work of these two departments, as well as lectures to engage professionals and publicise the work of the Clinic to the public. A little later in the 1920s Speech Therapy and Social Work were added to the services provided by the Clinic and towards the end of the decade a hostel was opened for patients from outside London.

By the end of the 1920s the building on Tavistock Square was no longer big enough. JR Rees, who had been deputy director since 1926, established an extension fund, called the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology, to raise money for new premises and on 9 August 1929 it was formally incorporated.

1932 to 1939: Reinventing ourselves

In November 1932 the Tavistock Clinic moved into a new building on the corner of Torrington Place and Malet Place. It was positioned alongside the University of London and renamed the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology. The building had previously been the stables for a Tottenham Court Road department store, but JR Rees had employed an architect to completely redesign the interior, creating modern consulting rooms, a specialist child play area, lecture theatre, library and canteen. They even had a primitive one-way screen for observation.

Hugh Crichton-Miller oversaw the move to the new building, but resigned shortly after with JR Rees becoming the second Director of the Clinic in 1933.

The move to Malet Place was part of a wider business plan to establish the Clinic as a postgraduate institution on the university scene. JA Hadfield, who had got university recognition for the Clinic’s Diploma in Psychological Medicine from the University of London in 1932, was made its Director of Education in 1935. He immediately established a two-year training course for doctors wanting to take up psychotherapy and created a wide programme of public lectures, the highlight of which was a week of lectures by Carl Jung.

In 1934, JR Rees pulled off a PR coup by successfully obtaining Royal patronage from the Duke of Kent. This patronage represented the Tavistock’s ‘arrival’ on both the medical and social scene.

During the 1930s the Tavistock Clinic underwent a major period of expansion. In the first year of its life, with seven doctors, the Tavistock Clinic had seen 249 patients. In 1939 there were 90 doctors and 1811 patients, with the Adults Department alone seeing 26,500 appointments the first half of the year.

1939 to 1945: World War Two

On 1 September 1939 Hitler’s tanks rolled into Poland and World War 2 began.

The Tavistock Clinic was evacuated to the Westfield Women’s College in Hampstead and during the war a number of women took charge. These included Mary Luff, Jane Isabel Suttie, Margherita Lilley and Rosalind Vacher.

Meanwhile, JR Rees became consultant psychiatrist to the Army at Home, responsible for the mental health of approximately three million people. Many key figures from the Tavistock Clinic joined him in the army, becoming what was known as the ‘invisible college’. Together they were responsible for a range of important innovations. Selection processes were re-structured to keep people that would be prone to breaking down away from active duty.

Wilfred Bion developed his famous leaderless group to revolutionise the process of officer selection. The ‘invisible college’ worked on: training and morale, the interrogation of prisoners, propaganda for the enemy and clinical support for the army. Bion again, with the help of John Rickman, instigated a major piece of work supporting returning soldiers and prisoners of war – known as the Northfield Experiment, it was short lived, but became the basis of much future group work and therapeutic communities. Then, at the end of the war, key figures of the ‘invisible college’ played a role in the de-Nazification of Germany, helping to select new members of the government and administration, and promoting democratic processes.

During the Second World War, 44 members of staff from the Tavistock Clinic, including 20 senior staff, were called up into active duty. As World War 2 came to an end staff began to think about the future. A new generation from the Tavistock Clinic was eager to apply the new concepts and ways of working that they had learned during the war to the peacetime environment.

1945 to 1947: Operation Phoenix

A new Interim Medical Committee was elected by the whole of the staff with Wilfred Bion as Chair to take the Tavistock Clinic forward. Under Bion’s leadership ‘Operation Phoenix’ was put into action. Radical democratic processes were instituted in the way that the Clinic was run that included the election of senior positions. New staff were co-opted from the military, particularly those who had worked on the War Office Selection Boards. These included: Eric Trist and Jock Sutherland, followed by John Bowlby. Bion initiated one of the most dynamic phases of the Tavistock’s history.

The Tavistock Clinic had suffered during the Blitz. Tavistock Square, Malet Street and the new building they had bought on Store Street, ready for further expansion, were all destroyed, along with most of the Clinic’s records.

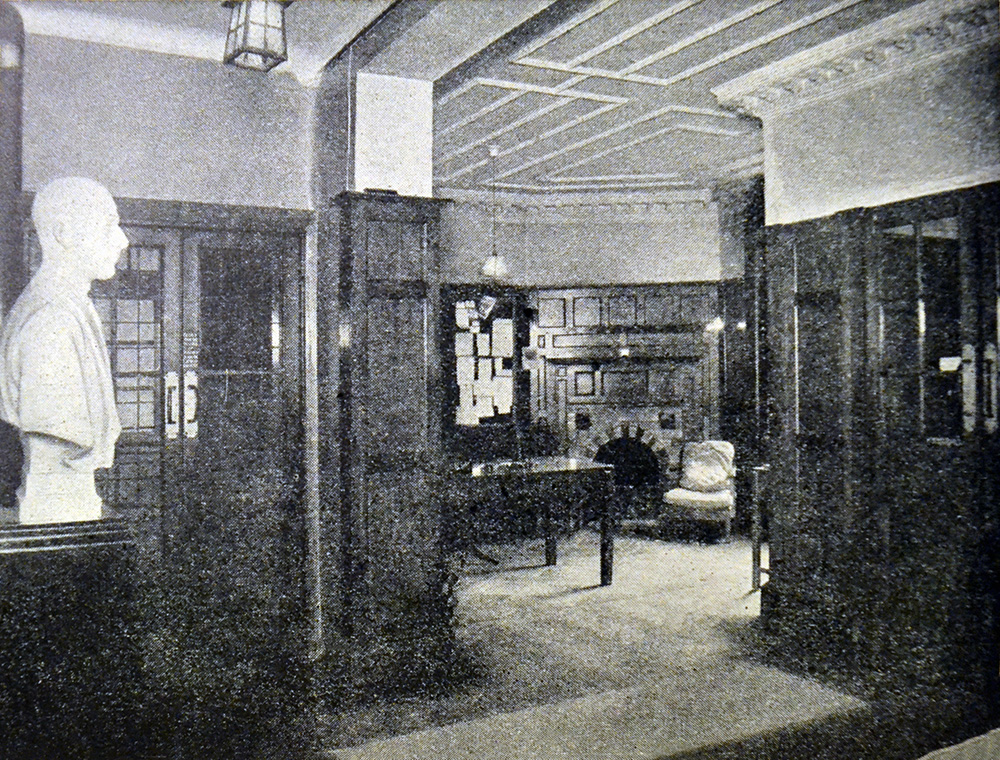

First order of the day was finding a new home and in August 1945 the Tavistock Clinic moved into 2 Beaumont Street (pictured).

During the war Bion and his colleagues had begun to look at social organisation, so once back at the Tavistock Clinic he created a study group on group dynamics that included John Rickman and Jock Sutherland. In 1946 this work gave birth to a new organisation: The Tavistock Institute of Human Relations (TIHR) . Created, in part, with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, it pioneered a multi-disciplinary and integrative approach to the behavioural sciences in relation to the workplace. The two organisations worked very closely together, sharing the same staff and same building.

At the same time the Clinic began preparations to join the new NHS. The Clinic as a whole expanded its patient base, opening itself up to patients from the whole income range. John Bowlby re-structured the Children’s Department. With the new colleagues from the military came a new spirit of professionalism. Many of the old colleagues from before the war left. This included JR Rees, and in 1947 Jock Sutherland became the new Director.

1948 to 1954: Joining the NHS

In July 1948 the Tavistock Clinic entered the NHS, coming under the Central Middlesex Group Hospital Management Committee of the North-west Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board. Joining the NHS exposed the Tavistock Clinic to a much larger and wider patient group. However, sacrifices had to be made as it was primarily the clinical work that the NHS took over. In order to keep its research and educational work alive this transferred to the TIHR and this kept the relationship between the two organisations extremely close.

During the late 40s and 1950s the Tavistock Clinic produced some of its most influential work. Bion initially continued to work on group dynamics, before his analysis under Melanie Klein led him back to working with individuals and developing concepts such as ‘containment’. Bowlby gradually developed ‘Attachment Theory’. This was supported by research from Mary Ainsworth., Mary Boston. and James Robertson particularly his production of the famous film A Two Year Old Goes to Hospital, which after several decades of campaigning changed the way that children’s departments operated, not just in the NHS, but around the world. Before the film, visits to children in hospital had been limited to an hour a day on Saturdays and Sundays, but in 1954 daily visits were introduced. At the same time the Clinic began to look at marital relations.

Within the clinic HV Dicks and Mary Luff developed marital services and externally Alison Lyons, Lily Pincus and Enid Balint developed the Family Discussion Bureau (later renamed the Institute of Marital Studies and now known as Tavistock Relationships), which became part of the ‘Tavistock family’ joining the TIHR in 1957.

In 1948 John Bowlby invited Esther Bick to develop a training course in child psychotherapy for the Children’s department and that led to one of the single most important developments to come out of the Tavistock Clinic: Infant Observation. In the training that she developed Esther Bick wanted to give students practical experience of infants, so she placed students in families as observers.

The first Tavistock Child Psychotherapy course which began in 1948 and was made up of an unusually talented cohort of students that included Martha Harris, Frances Tustin and Isca Wittenburg, who not only took part in the course but contributed to it. The results of this work were eventually formalised in Esther Bick’s landmark paper on Infant Observation in 1964 and subsequently led to several Tavistock textbooks on the subject: (Miller, Rustin, Rustin and Shuttleworth (1989), Reid (1997), Piontelli (1996) Briggs (2002), Sternberg (2005), Urwin (2012), Adamo and Rustin (2019).

1954 to 1965: A period of consolidation

In 1954 in Britain institutionalisation was still the main method for dealing with mental illness. There were 154,000 patients in asylums, which were overcrowded and underfunded. These contained 40 per cent of the NHS inpatient beds, but received only 20 per cent of the hospital budget. The second half of the 20th century saw a fundamental shift in the way people with mental health problems were cared for.

In 1956, administration of the Tavistock Clinic shifted to the Paddington Group Hospital Management Committee, which already administered the Portman Clinic and the Child Guidance Training Centre. Plans for the future development of a new building at Belsize Lane were successfully submitted.

Working within the NHS and taking a much wider patient group affected learning and practice within the Tavistock Clinic too. Michael Balint began work on short treatments, later supported by David Malan. Isabel Menzies Lyth undertook ground-breaking research that showed social defence processes involved in working in stressful situations.

Michael Balint also began developing support groups for medical practitioners. Balint groups remain an important support and training resource for anyone working in the NHS.

In 1957, the Tavistock Institute launched its first full scale experiment in group relations in partnership with the University of Leicester. Leicester conferences continue to this day and are replicated all over the world, including several times a year within the Tavistock and Portman. The wartime experiments in group treatment and officer selection were the source of this radical innovation in social learning.

In 1959, a pilot Adolescent Unit was created, led by Derek Miller and Dugmore Hunter, and in 1960, this became the Adolescent Department which was situated on one floor of a leased building at Hallam Street and was run with the part-time loan of staff from other departments. Originally the idea had been to provide support for gifted but inhibited students, but the focus quickly shifted towards delinquency. Eventually the department would become the home of much innovation at the Tavistock Clinic and produce key thinkers such as Anton Obholzer and Margot Waddell.

During the 1960s, the Tavistock Clinic became more integrated with the wider mental health movement with former members of staff taking up senior positions in other organisations and the Tavistock Clinic employing staff from a wider range of sources. International links began to be built with staff lecturing and training abroad, while the Tavistock Clinic itself started to receive more international visitors, lecturers and trainees.

In 1960 the Tavistock Clinic was visited by Enoch Powell, the then Health Minister, who was impressed by what he saw. The Tavistock Clinic provided a model of non-hospital based care and high quality services integrated multi-disciplinary teams. Not long after, the plans for the Tavistock Clinic’s new building were approved. The Board’s architect, FAC Maunder, began work.

In 1961 Enoch Powell delivered his ‘Water Tower’ speech which underlined the government’s policy of closing asylums and moving care into the community. It followed closely from the 1959 Mental Health Act, which identified the community as the most appropriate place of care for people with mental health problems and importantly, stated that people who were sane, but labelled ‘morally defective’ could no longer be admitted to an asylum.

1965 to 1970: Moving to Hampstead

In 1965 the foundation stone of the new building at Belsize Lane was laid by JR Rees and on 4 May 1967 it was opened by Princess Marina. The Tavistock Clinic (including the new Adolescent Department, which merged with the Young People’s Consultation Centre in Hampstead), the TIHR (which included the Institute of Marital Studies), and the Child Guidance Training Centre moved in.

John Bowlby retired as head of Children and Parents in 1968, after 22 years of service and was succeeded by Marion McKenzie. After overseeing the move to the new premises JD Sutherland also resigned in 1968, to take up a teaching appointment at the University of Edinburgh. On 1 August 1968, Robert H. Gosling took charge of the Tavistock Clinic under the new title of Chairman of the Professional Committee after winning the unanimous vote of his colleagues.

Robert Gosling was the first and foremost of the new generation of psychiatric staff that shaped the Clinic after the retirement of Jock Sutherland. His style was a much more facilitating and participatory one and led to a flowering of creativity in the institution.

In the period after the war the Tavistock Clinic retained a position of being staunchly independent and associated with the development of object relations theory, but during the 60s it became known as a Kleinian institution, thanks to the influence of key figures such as Wilfred Bion, Donald Meltzer, Martha Harris and Isabel Menzies Lyth.

In 1969, further administrative changes took place within the NHS and the Tavistock Clinic came under the St Charles Hospital Management Committee. Under Robert Gosling’s leadership the Tavistock Clinic flourished once again and went through another period of significant expansion.

Throughout his career Robert Gosling was closely involved with group relations. He participated as a consultant in the Leicester Conferences and he wrote the seminal paper on very small groups. It is not surprising that under his leadership the relationship with the TIHR remained strong.

In 1970 the Portman Clinic moved to its current location on Fitzjohns Avenue, next door to the Tavistock Clinic.

1970 to 1983: Child development comes to the fore

During the 1970s the Department for Children and Parents flourished. Although Bowlby had retired he published his definitional trilogy on attachment: Attachment (1969), Separation (1973) and Loss (1980). These were hugely influential and brought global attention to what the Tavistock Clinic was doing.

Martha Harris also wanted to see the influence of the Tavistock extended. In the mid-70s, believing that child development information should be more widely available for professionals working with children, she initiated the publication of the hugely successful ‘Understanding Your one/two/three/etc Year Old’ series with Elsie Osborne. She then opened up the pre-clinical seminars to non-medical professions, significantly expanding the teaching that the Clinic provided.

In 1971, an important technical innovation – video – came to the Tavistock Clinic. Initially it was frowned on for clinical work, but James and Joyce Robertson again played a key role in getting it established as an invaluable analytic tool.

Also in the early-1970s, Chris Dare and John Byng-Hall, who had both trained at the Tavistock, in child and adolescent psychiatry, began to develop Systemic Family Therapy. John Byng-Hall initially organised a Family Therapy Workshop in the Adolescent Department and a research group. They invited people from the US to talk and give short-term courses, with Sal Minuchin, taking a sabbatical at the Tavistock Clinic to write Families and Family Therapy (1974). In 1974 John Byng-Hall and Rosemary Whiffen became co-Chairs of the Family Therapy Programme. The first Family Therapy Training Course in the UK was organised at the Tavistock Clinic in 1975 and the first International Forum for Family Therapy Trainers was organised in 1979. It was the first family therapy training established in the UK.

In 1976, Emanuel Lewis published ‘The Management of Stillbirth: Coping with an Unreality’. Working from 1968 to the 1990s Lewis and Stanford (Sandy) Bourne highlighted the trauma of stillbirth and its wider impact on families. The disposal of stillborn foetuses, without contact with the parents, remained routine practice until the later part of the century. Their work showed that not only did this create immediate problems for grieving, but could also have significant impact on subsequent siblings.

In 1979, Robert Gosling retired from the leadership of the Tavistock Clinic, due to his increasing deafness. Alexis Brook took over as Chair of the Professional Committee.

Alexis Brook had served under JR Rees in the Royal Army Medical Corps from 1944 to 1947. He trained in psychiatry at the Maudsley and Napsbury Hospitals, before going to the Cassel Hospital. At the Tavistock he tried to establish greater links with wider medical practice. He looked at the relationship between stress and occupational health. He also sought to embed treatment in the community and develop an outward-looking community-based approach to mental health with therapists working alongside GPs.

In the Adult Department, David Malan’s detailed research into short-term therapy had started to show the effectiveness of brief therapy and in the Department for Children and Parents the social workers, led by Joan Hutton established a brief therapy team.

The Mental Health Act 1983 introduced the issue of consent into the treatment of mental health.

1983 to 1987: Threats, mergers and acquisitions

At the start of the 1980s, the newly elected Conservative government had come to power with a mandate to reduce public spending. This cut across all areas of public services and the NHS was not exempt. It was against this background that following the Griffiths Report in 1983 the NHS saw a radical change of culture with the introduction of General Management, where for the first time clinicians and professional staff had to answer to managers.

Within the Department of Health there was a general perception that psychotherapy was an expensive luxury. The Seymour Commission was set up to look into this. Alexis Brook from the Tavistock Clinic and Rob Hale (the then Chair of the Portman) were both on the Hampstead Health Authority and both saw it as a potential threat.

To counter the perceived threat the Portman Clinic undertook a cost-benefits analysis on the impact of shutting down the Tavistock and Portman Clinics and was able to show that such a closure would cost more than would be saved, in terms of the impact on other institutions.

In the mid-1980s the Child Guidance Training Centre (CGTC) , which had been sharing premises with the Tavistock Clinic at Belsize Lane, had its funding cut. The decision was taken to merge the CGTC with the Department for Children and Parents at the Tavistock Clinic and between 1984 and 1985 departmental chair Judith Trowell and CGTC social worker Gillian Miles oversaw the somewhat painful transition.

The CGTC had existed since 1928 when it was founded by Dr William Moodie and had its own proud traditions. John Bowbly had trained there and it had a key role in establishing multi-disciplinary teams for supporting children and their families.

When it joined the Tavistock, the merged department was renamed the Child and Family Department and became the largest department at the Tavistock Clinic. The merger also bought Gloucester House, or the Day Unit, as it was known at that time under the Tavistock Clinic.

Alexis Brook stepped down in 1985 and Anton Obholzer took up the leadership of the Tavistock Clinic. A South-African by birth, with Austrian lineage, Anton Obholzer is the only Chief Executive to have worked in every department of the Tavistock Clinic.

Working closely together, Rob Hale and Anton Obholzer began a strategy of making the two clinics more outward facing by building support at the Houses of Parliament and generally publicising the work of the two institutions.

When it was eventually published, the Seymour Report was quite supportive of the Tavistock and Portman clinics, though it made a number of recommendations, particularly in regard to education.

In 1987 Mervyn Glasser took over leadership at the Portman Clinic and Rob Hale moved to the Tavistock Clinic taking up a role as Dean.

1980s: Education, education, education

The Seymour Report had stated that although many of the courses at the Tavistock Clinic had professional recognition, training at the Tavistock Clinic also needed academic accreditation. A suitable academic partner had to be found and approaches were made to the University of East London (UEL).

The timing was good as the UEL had recently broken from the University of London’s degree structure and had started working with the Council for National Academic Awards, so when discussions began with the Tavistock Clinic there was already a supportive climate of opinion, and an academic apparatus for course development and validation in place.

As is often the case at the Tavistock Clinic, social work led the way. Joan Hutton wanted accreditation for the post-qualifying social work course. At UEL Carol Satyamurti (the poet) and Michael Rustin were able to offer the social workers an add-on doctorate that was validated by UEL. This pilot resulted in a positive synergy that led to more than 20 Masters level programmes being established between the UEL and Tavistock Clinic.

Many of the established professional clinical training courses, such as Interdisciplinary training in adult psychotherapy (M1), continued as before, without being linked to the universities, and some still do. The clinical trainings are all accredited by professional organisations.

With university accreditation in the late 1980s, the Tavistock Clinic had begun to take itself seriously as a higher education institution and bid for an NHS national contract for training. This entailed that training would need to be transferred back from the TIHR to the Tavistock Clinic.

1988 to 2002: Threats, mergers and acquisitions part two

In 1988, Margaret Thatcher announced a significant review of the NHS as a whole and from this two white papers were published that outlined the introduction of an ‘internal market’ that introduced competition into the NHS and proposed a split between purchasers and providers of care that continues to this day.

As part of the same legislation, in 1990 NHS trusts were introduced under the National Health Service and Community Care Act. The Professional Committee recognised that unless the Tavistock Clinic became a trust itself, it would probably be swallowed by another trust. In such a situation, the best that could be hoped for was that the Tavistock Clinic would become the standard NHS mental health arm of another organisation and would lose its autonomy.

The changes required to become an NHS trust were significant. Historically most of the administrative functions of the Tavistock Clinic, HR, finance and so on, had been provided by their health authorities. In the 1970s the Tavistock Clinic only had one administrator and one training administrator, now they needed to create all the standard administrative functions necessary to function as an independent organisation and with no extra funding to do so.

The first attempt to become a trust was not successful.

In 1994, Rob Hale took over leadership of the Portman again and by that time the situation was serious. It was an era of aggressive takeovers and asset stripping. The Tavistock and Portman Clinics both had properties in prime locations making them targets.

With Rob Hale back at the Portman it became possible to broker a merger between the two organisations, but with them remaining as two separate clinics within one trust, as they prepared their new bid to become an NHS trust.

Later that year, as part of the fourth wave of applications, the clinics became the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust. Anton Obholzer became Chief Executive of the new trust and Tony Vineall, previously of Unilever, became the Chair of the Trust Board.

Although this period of transition was enormously stressful there were some notable developments. Following the sinking of the Herald of Free Enterprise in 1987, two members of the Adult Department went to Dover to offer backup support. This was the first stage in the formation of the Unit for the Study of Trauma and its Aftermath. Eighteen months later a Trauma Unit led by Caroline Garland was founded in the Adult Department, with ‘seedcorn’ money allocated by Anton Obholzer.

In 1992 Valerie Sinason published Mental Handicap and the Human Condition, new approaches from the Tavistock Clinic. This work was very much rooted in the Trust’s strong history of working with developmental issues in child education services and by the 1990s the Trust were a leader in the field. By the end of the 1990’s we were clearly differentiating two groups: learning difficulties and autism. This led to two separate streams of work: one on autism chaired by Anne Alvarez and Sue Reid, and one on learning disabilities chaired by Valerie Sinason and Sheila Bichard. These two teams developed their expertise further and developed specialist training and education programmes, as well as a range of significant papers and publications, including: Autism and Personality (1999) by Anne Alvarez.

At the same time as the Tavistock and Portman became a Trust, the national training contract was awarded to the Trust. Margaret Rustin, who had become Dean in 1994, worked with UEL to develop five doctorate courses (which also functioned as research degrees). At one stage there were more than 1,000 Tavistock students enrolled on UEL courses and 70 per cent of the Tavistock Clinic’s income was coming from training.

With increasing pressure on space at the Tavistock Centre, TIHR moved to new premises in central London. The relationship between the Tavistock Clinic and the TIHR had been an important and fruitful source of ideas for almost fifty years. Training and research was very much what kept the two organisations joined, so when the training function was moved back to the Tavistock Clinic the two organisations began to move apart. The Institute of Marital Studies initially remained part of the TIHR, but stayed at the Tavistock Centre.

Also in 1994, Anton Obholzer supported Jon Stokes to set up Tavistock Consulting. The aim was to bring together psychoanalysis and an understanding organisations from a systemic point of view to develop an individual coaching and consulting service for organisations and leaders. The original organisation was created by Jon Stokes with David Armstrong and Clare Huffington. Tavistock Consulting has gone on to become a successful organisation and an integral part of the Tavistock and Portman. Its work has led to the development of one of the Trust’s most popular courses: Consulting and leading in organisations (D10).

The Gender Identity Development Unit was founded in 1989 at the Department of Child Psychiatry at St Georges Hospital St George’s by Domenico Di Ceglie, of the Tavistock’s Adolescent Department, to offer support to young people experiencing distress about their gender identity. In 1994, GIDS moved to the Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust, initially taking up residence in the Portman Clinic. Since 2009 the service has been nationally commissioned by NHS England.

In 1999, Anton Obholzer’s continuing emphasis on promoting the good work of the clinic to the media bore fruit with the BBC’s six-part series, The Talking Cure, coinciding with the publication of a book of the same name. Although many at the Trust were concerned about the impact of media attention, the series was hugely successful in raising awareness of the work of the Trust. This was revisited in 2016 when the Trust once again let the cameras in. This time it was Channel 4 which commissioned a three-part series Kids on the Edge, produced by Century Films.

In 2001, a Centre for Mental Health in Nursing was set up jointly with Middlesex University to provide new training programmes in nursing.

In response to a call for research, also in 2001 Phil Richardson and his team began work on the important and influential Tavistock Adult Depression Study. This long-term study was taken over by David Taylor in 2007 after Phil Richardson’s death. Felicitas Rost is currently the lead researcher. In 2015 it produced its seminal paper Pragmatic randomized controlled trial of long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression: the Tavistock Adult Depression Study (TADS), published in World Psychiatry.

As part of the national training contract with the NHS the Tavistock Clinic needed to evidence that they were changing the national pattern of training and set about developing regional centres. In 2002 The Northern School of Child Psychotherapy was established in Leeds and a course was developed in Birmingham.

2002 to 2019: Into the 21st century

In 2002, Anton Obholzer retired after playing a crucial role while at the helm of the Trust. He was succeeded by Nick Temple.

Nick Temple had been a consultant at the Tavistock Clinic since 1989, with Margot Waddell. he had been a founder and joint editor of the Tavistock Clinic Series since 1994, and had also been a consultant at the Portman in the early 80s. He was an influential member of the Adult Department and had been a Vice Dean and Chairman of Professional Committee. Staff regarded him as Tavistock through and through: a safe pair of hands rather than the threat of an outsider.

In the early years of the new century, equalities became a bigger issue at the Trust. Although equalities legislation had been put into place with the Race Relations Acts of 1965, 1968 and 1975, following the death of Stephen Lawrence, the 1999 Macpherson Enquiry found strong evidence of continuing institutional racism. The report from the enquiry made 70 recommendations to tackle racism and improve accountability in public bodies. Agnes Bryan and Inge Britt-Krause were appointed to tackle these issues by the then Dean Andrew Cooper. This made Agnes Bryan the Trust’s first BAME senior manager.

Not long after this Frank Lowe was appointed and began work developing Thinking Space to look at racism, particularly the unconscious aspects of racism and the distinctions made by Bion between ‘knowing’ and ‘knowing about’. Originally these meetings were held in the institutional space of the Tavistock Centre, but then following the riots of 2011 Frank took Thinking Space to Tottenham instigating a community development approach to improving mental health and community well-being by empowering communities to become agents of change themselves.

This was followed by a wide-ranging project led by Louise Lyon, Trust Director and Chair of the Equal Opportunities Committee, in collaboration with Stonewall, spanning across HR practices, communications and our training curriculum to tackle inequalities relating to LGBTQI+ status and root out the pathologisation of homosexuality in our recommended texts and teachings.

In 2002, Health Secretary Alan Milburn introduced the idea of foundation trusts, with the first ten announced in 2004. Foundation trusts provided more managerial and financial freedom than NHS trusts. They represented a significant change in the way in which hospital services are managed and provided in the NHS. The Tavistock and Portman began the intense and challenging application process to become a foundation trust. It successfully became the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust in 2006, one of the first mental health trusts to do so.

Under foundation trusts, the functions of hospital administration became more specialised. Reporting lines changed too. Finances were answerable to Monitor, clinical practice to the CQC. Budgets increasingly belonged to individual trusts. National budgets diminished and became fragmented.

In 2003, systemic therapy was recognised as one of the Trust’s six core disciplines, with systemic therapy having been in existence and running courses at the Trust since the 1970s and having established the first ever doctorate in systemic family therapy, in partnership with UEL in the 1980s.

In 2004, the Institute of Marital Studies expanded by taking over some of the functions of London Marriage Guidance and enlarging its range of services beyond marriage to include couples. In recognition of this, it changed its name to the Tavistock Centre for Couple Relationships (TCCR). It had already separated from the TIHR 1979, becoming an independent company operating under the overarching charity the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology. In 2009, following further expansion, the TCCR moved to new premises in central London, expanded to a second site in Liverpool Street in 2010, and renamed itself Tavistock Relationships in 2016.

In 2005, the Tavistock and Portman became the main provider of child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) for Camden, although we had been providing many aspects of CAMHS services and work in schools in Camden for several decades. Our MALT (Multi Agency Liaison Team), led by Rita Harris and Andy Wiener, had already pioneered integrated CAMHS and local authority services and the success of this model led to us fully embedding workers in schools across Camden from 2009.

In 2008, Matthew Patrick succeeded Nick Temple, when he retired as Chief Executive. Matthew Patrick had trained as an adult psychiatrist at the Maudsley and Bethlem Royal Hospitals and in psychotherapy in the adult department at the Tavistock. For many years he combined clinical work and developmental research at UCL. He joined the Tavistock and Portman staff in 1996 as a consultant. Under Matthew Patrick’s leadership there was another period of consistent growth with both clinical and training and education portfolios expanding.

A new service, the Family Drug and Alcohol Court (FDAC) , was established by the Tavistock and Portman in 2008 to help parents stop using drugs or alcohol and keep families together. Instead of the usual care proceedings, a family chosen for the FDAC programme goes through a very different therapeutic process co-ordinating a range of services around the family to help tackle drug and alcohol problems. At the same time it redefines the role of the judge within a problem-solving approach.

In 2009 the Tavistock and Portman founded the City and Hackney primary care psychotherapy consultation service (PCPCS) to help GPs manage patients with complex needs. The PCPCS was initially located in the ground floor annexe of Shoreditch Health Centre and its founders included: Phil Stokoe, Louise Lyon, Rob Senior and Rhiannon England, though its theoretical basis is rooted in the research and work of Michael Balint and David Malan, particularly around brief therapies. Joint consultations are held in GP surgeries and oriented towards providing talking therapies to resolve issues rather than medication. In 2013 the PCPCS won a Royal College of Psychiatrists Award and in 2015 it won a British Medical Journal Award.

The success of the PCPCS influenced the development of services elsewhere. In 2015 we won a competitive tender to provide a sister service was created in Camden, known as the TAP (Team around the practice), in partnership with Camden and Islington Foundation Trust and Hillside Clubhouse. The TAP also works with adults in the familiar environment of their GP practice to manage their mental health needs, providing psychological therapy and social prescribing.

Between 2013 and 2020 the Family Nurse Partnership National Unit joined the Tavistock and Portman, leading the delivery of a national home visiting programme for first time mums. In the Family Nurse Partnership (FNP) programme, specially trained family nurses visit young mums regularly at home, from early in pregnancy until the child is two to help improve pregnancy outcomes, child health and development, and improve the parents’ economic self-sufficiency. The National Unit provides strategic direction for FNPs in England and has trained over 1,000 family nurses and supervisors so far. In 2020 it moved to Public Health England.

In December 2013, Paul Jenkins became the new Chief Executive of the Tavistock and Portman, succeeding Matthew Patrick. Paul Jenkins had a significant public sector career. He was awarded an OBE in 2002 for his role in setting up NHS Direct. Paul had then worked in the third sector as CEO of Rethink Mental Illness, taking an active lobbying role and campaigning to end mental health stigma and discrimination through the national Time to Change Campaign, run in partnership with Mind. He is the first non-clinical Chief Executive and the first not to be drawn from the Tavistock Clinic’s own staff.

Following on from the work of the Trust’s CAMHS and MALT (Multi Agency Liaison Team) teams, we refined our systemic approach to emotional well-being services for young people and linked up with the Anna Freud Centre to develop a whole system approach that became the THRIVE model, launched in 2014.

The Trust then received funding to develop a community of practice along with the i-thrive academy, which now has 76 CCG members and is clinically-led by our current Child, Young Adult and Families Director, Rachel James. It has been cited as a model of good practice in national NHS strategies, green papers and long-term plans.

In 2017, the Charing Cross Gender Identity Clinic joined the Tavistock and Portman. GIC had been founded in 1966 by Dr John Randall and is the oldest gender identity service in the UK. It was established as part of the Charing Cross Hospital in the West End and moved with it to Fulham in 1973. In 2020 it moved to a new location on Finchley Road.

Also in 2017, the Trauma Unit provided support to a number of front-line services after the Grenfell fire. Since Caroline Garland’s retirement in 2008, Dr Jo Stubley had taken over the leadership of the Trauma Unit. The Unit broadened its scope and developed expertise in addressing complex and developmental trauma, working with asylum seekers and refugees, veterans and survivors of childhood abuse.

Our work delivering CAMHS in schools in Camden influenced the CAMHS Green Paper and in 2018 we were successful in gaining trailblazer status for both our CAMHS in Schools and our wait time initiative. Waiting times in Camden had for some time been in the top 5% shortest nationally, according to independent benchmarking, as a consequence of implementing Thrive across our services.

In May of 2019 funding of £15 million was announced to expand promising innovative approaches to keeping families safely together. The aim was to provide an evidence-based approach to family justice and was modelled on the Trust’s Family Drug and Alcohol Courts (FDACs) and a programme known as Family Group Conferencing.

Centenary talks

Watch our series of centenary talks on our YouTube channel.